When school began this year, I looked at my small classroom in despair. I had 30 students on each period’s class list and an exhortation to fit all of them in my room ASDAP (as socially distanced as possible), which meant two feet apart. It’s been two weeks since that day, and I have yet to have a full class of students. Every period of every day is missing a minimum of three students, who are home because family members have tested positive. This has led to two unprecedented situations: first, a significant portion of students are at home but healthy and able to learn; and second, there is a very real chance that our class will need to go remote for short intervals of one to two weeks. The shifts between remote and in person adds a layer of additional social emotional needs for students that add complexity to planning.

In uncertain times, educators are faced with the need to build robust, inclusive digital learning environments while trying to navigate in person teaching with children who have not been in a “normal” classroom environment for more than 500 days. Balancing the resultant myriad of responsibilities is difficult to impossible, and teachers must work together to survive. Unfortunately, unprecedented times mean that there is little comprehensive information to go by when planning for this type of collaboration. However, we can piece together a set of practices from tools that represent the different portions of this challenge: collaboration in planning, planning for diverse populations, and planning during crises.

Building Online Courses

Best practices for online course creation often center around ways in which individuals on online course creation teams can collaborate most efficiently and effectively. This includes ensuring that all team members understand the expectations of the team and their role within the team, that the team has clear leadership, and that there is both a clear goal and flexibility within that goal (Hixon, 2008). Establishing and reinforcing these three elements of a planning team is one way to ensure that teams building online courses do so effectively. However, other approaches have also proved effective, which is important since educators often find themselves building their online courses alone.

Stephen Sommer at the University of Colorado took an innovative approach to online course creation and collaboration: including students in the design of the course. Through affinity groupings for small group work, asking students to synthesize materials, and frequent feedback, students built the course as it progressed. By involving students intimately in the creation of the course they were taking, Sommer “created an environment where all students had a voice, engaged in the course material, and had a rich learning experience” (University of Colorado, 2020). With this approach, Sommer transformed a course design process that would have otherwise been an individual process into one in which his students become a course design team.

Sommer’s approach corresponds with the inclusive practice of increasing engagement through responsive learning. This practice is a way to address one of the obstacles for many diverse learners: a mismatch between the method of instruction and learning needs. This mismatch causes learning breakdown, which occurs “when students face barriers to learning, feel marginalized by the learning experience offered or feel that their personal learning needs are ignored” (Inclusive Design research Centre, 2021). Teams working collaboratively to respond to learning needs can build effective instruction.

Building Inclusion

Once the building team best practices are in place, the task of building inclusion into remote learning begins. Perhaps the best, and simplest advice for schools regarding building inclusion into tumultuous learning environment comes from New South Wales, and is twofold: be proactive, and learn from other industries (Alchin, 2021). The importance of proactively folding inclusion into online learning environments was never more evident than in March 2020 when schools around the nation suddenly found their doors closed and their remote learning programs out of compliance with the IDEA act. With confusing guidance from the Department of Education, many districts simply stopped requiring education for all students, as exemplified by the deputy chief of the School District of Philidelphia, Monica Lewis’ statement at the time that “If we can’t provide for all, we can’t provide formal education for some” (Quinton, 2020)

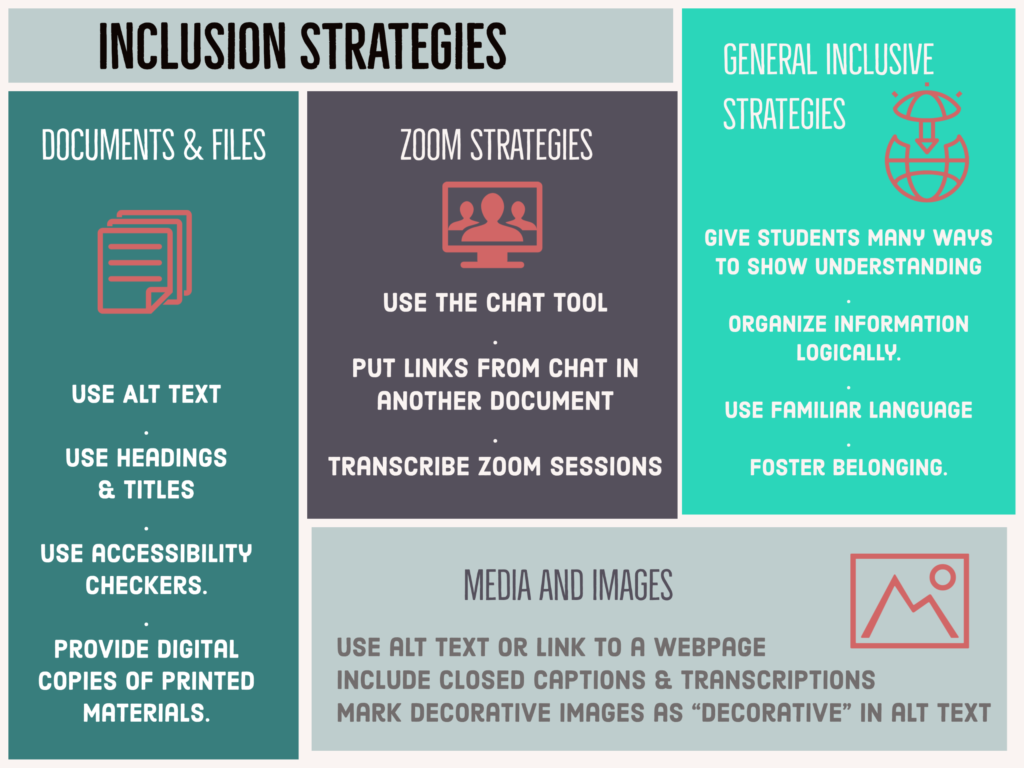

Planning proactively is essential. As we return to digital and in person classroom, educators have an opportunity to think ahead to the possibility of remote learning re-emerging and ensuring that their digital learning platforms are inclusive so that all students can learn equally even if the environment changes. Proactively weaving inclusivity into the core of learning requires a shift in understanding the tools and structures of digital learning toward one that centers on “awareness, adaptation, collaboration, and flexibility” (Inclusive Design Research Centre, 2021). Brown University’s Digital Inclusion and Accessible Learning Guide provides several practical ideas for educators to make specific platforms inclusive (Brown, 2021).

Learning from other industries can be a risky undertaking in education because in some ways the values of other industries don’t translate perfectly to the unique situation of education. However, education can benefit from reflecting on the thought that has gone into ensuring that technology tools are fully accessible that some technology organizations have undertaken. According to Alchin, “both the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Apple have developed design resources that are extremely useful reference points for educators in designing inclusive digital learning materials and environments” (2021). The W3C developed four principles for content design that are particularly useful in ensuring that digital education is inclusive. These principles assert that both content and the method by which users access and interact with the content be: “perceivable, operable, and understandable . . .[and] robust enough that if required, it can be reliably used with assistive technologies such as a screen reader or switch.” (Alchin, 2021). Checking digital education content for these four elements ensures that the lesson and materials are accessible by individuals with disabilities and include meaningful learning.

Building an inclusive learning environment in turbulent times means overcoming obstacles that would not seem as challenging otherwise. The greatest of these is curriculum that does not allow for the flexibility required to meet the needs of diverse learners. The New South Wales report explains that “inflexible curriculua. . .[raises] unintentional barriers to learning. . . learners who are gifted and talented or have disabilities, are particularly vulnerable” (Alchin, 2021). Building flexibility into an inflexible curriculum ranges from the most drastic changes to those that merely adjust existing curricula. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) presents the most radical departure from existing curriculum. A less drastic measure includes minor adjustments to curriculum, including:

- “set explicit student expectations” (Columbia CTL, 2021).

- “giving students multiple means for demonstrating understanding” (Brown Digital Learning, 2021).

- “provide information in a logical flow” (Brown Digital Learning, 2021).

- “foster belonging.” (Brown Digital Learning, 2021).

- “Reflect on one’s beliefs about teaching (online) to maximize self-awareness and commitment to inclusion” (Columbia CTL, 2021).

To successfully build learning environments that meet the needs of diverse learners, are inclusive and welcoming, and can quickly change from in-person to remote during frequent changes in this uncertain time, educators must work together in teams, gather ideas from outside of the education industry, and creatively overcome obstacles.

Resources

Alchin, G. (2021, August 4). Designing inclusive digital learning environments. NSW Department of Education & Communities. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/past-issues/vol-32–2013/designing-inclusive-digital-learning-environments

Brown Digital Learning Design. (2021). Digital Inclusion & Accessible Learning Design. Brown University. https://dld.brown.edu/resources/guides/hybrid-teaching/digital-inclusion-accessible-learning-design

Columbia CTL. (2021). Inclusive Teaching and Learning Online. Columbia University. https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/inclusive-teaching/

Hixon, E. (2008). Team-based online course development: A case study of collaboration models. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 11(4), 1–8. https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/winter114/hixon114.html

Inclusive Design Research Centre. (2021). Where to begin? | Inclusive Learning Design Handbook. The Floe Project. https://handbook.floeproject.org/introduction.html

Quinton, S. (2020, March 24). Switch to Remote Learning Could Leave Students With Disabilities Behind. The Pew Charitable Trusts. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/03/24/switch-to-remote-learning-could-leave-students-with-disabilities-behind

University of Colorado. (2020, October 24). Collaborative course design fosters an inclusive learning environment. Center for Teaching & Learning. https://www.colorado.edu/center/teaching-learning/2020/07/02/collaborative-course-design-fosters-inclusive-learning-environment-students